Field Notes from India: Spontaneity is its Own Reward

A whirlwind encounter with Jaipur’s living history

It is in all of us to defy expectations, to go into the world and to be brave, and to want, to need, to hunger for adventures. To embrace the chance and risk so that we may breathe and know what it is to be free.

~Mae Chevrette

Yes, you read that right—I’m in India for a short spell. I’d been in Kenya less than a week when my host asked if I’d like to accompany her on an impromptu jaunt to Jaipur, Rajasthan, India, to collect supplies for her lodge. There was only one answer. And, so it is. I’m now writing to you from a breakfast table here in Jaipur.

Admittedly, the travel was not inconsequential, my regular routines have been disrupted, and rather than slow and earth-connected, this trip is a deep immersion in the caldron of humanity and the built environment. Still, it’s a way to experience another part of the world. I've been to India once before (I spent a semester teaching a course on sustainability and wilderness skills in the Himalaya (Ladakh) with a little time in Delhi), but this is a big country and a big world, and there’s so much more to learn.

It’s been a whirlwind of monsoon; full-on death-defying street travel; a disturbing amount of trash, poverty, and unsanitary conditions; stark inequality; and a portrait of a once-luxurious city in physical decay. It’s also been a time of connection with wonderfully warm and welcoming people, an opportunity to be awed by the physical grandeur—despite it’s mostly decaying condition—of the capital city of an ancient kingdom, and a deeply sensory gathering of form, color, history, culture, and religion that will take time to process and integrate.

Digging into Jaipur's rich history is far beyond my capacities here and now. Still, there are a few fascinating tidbits that resonate with my background in urban planning, earth-based practices, and water—always water.

Jaipur is an ancient walled city meticulously planned and built by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II, the ruler of the Amer (later Jaipur) kingdom, within a four-year span between 1727-1731 CE (meaning Common Era, denoting the same years as AD (Anno Domino) but inclusive of diverse religious and non-religious perspectives). The city was meant to be the royal capital and a commerce center. Its design follows the principles of Vastu Shastra, a traditional Hindu architectural science rooted in ancient texts that harmonizes design with nature—incorporating the natural forces of sunlight, wind, earth, and gravity, the cardinal directions, and the flow of energy. By adhering to these principles, Jaipur was to be a city where residents would experience health, wealth, and prosperity stemming from balanced interaction with the five basic elements of nature: earth, water, fire, air, and space.

These design principles are on display in the gridded layout of the city, with the royal palace located in the center of a nine-square mandala and the city built around it. The principal streets run east-west and north-south to maximize sun exposure—avoiding low angle sun during sunrise and sunset and allowing the sun to warm the buildings during early mornings while preventing the evening sun from scorching them during the summertime.

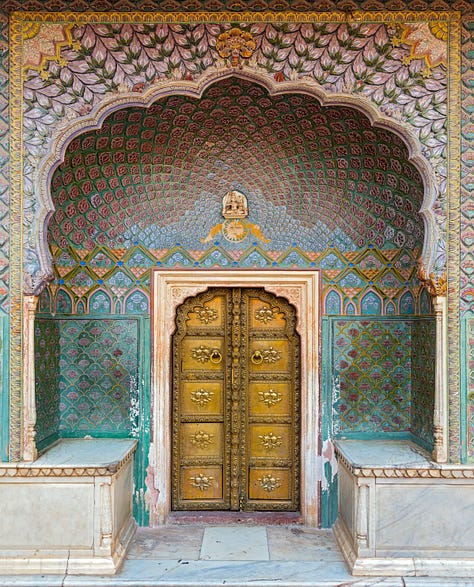

The orientation of three of the city’s seven gates honor celestial energies: The eastern gate—Suraj Pol (Sun Gate)—greets the rising sun and leads to the Sun Temple; the western gate—Chand Pol (Moon Gate) acknowledges the setting moon; the northern gate—Zorawar Singh Pol, also known as Dhruv Pol, refers to the Pole (or North) Star and faces towards the ancestral capitol of Amber. Four gates—Kishan Pol, Naya Pol, Shiv Pol, and Ram Pol are named to commemorate places or figures and protect the southern flank of the city. Two additional major gates and numerous minor gates have been added in more recent times. Stunning arches are found everywhere—as doorways, windows, gates, wall inserts, you name it.

According to Samidha Mahesh Pusalka1, well-known British historian George Mitchell says of the walled city of Jaipur:

is not only the best-preserved example in India of a town laid out according to traditional Hindu theory but embodies ideas that may have travelled to India by way of the Islamic invasion, and which are pre-Islamic in origin. These ideas are concerned with linking the city with the heavens, either by recreating the structure of the universe in the form of a sacred mandala or by incorporating into the city how the heavens may be observed, and the movement of stars measured.

On some counts, Jaipur is thriving as a center of commerce. World-renowned for its handmade textiles, lapidary arts (gem cutting), and jewelry fabrication, it has a robust tourist economy and a flourishing merchant class. My aesthetic sensibilities have been delighted at every turn.

At the same time, wealth inequalities are dramatic2 and rapid population growth (the city has almost doubled in size since 2000—from ~2.5 million in 2000 to ~4.4 million today) has outpaced city planning and services. Simply looking around will tell you much of the story. Buildings and walls are crumbling, people and animals are living in littered streets, traffic is a mess, and the signs of animal and human waste are apparent.

A little research (into one of the issues I know well) reveals more: Jaipur relies heavily on groundwater and surface water stored behind the Bisalpur Dam. The area is naturally water-scarce and over-extraction of groundwater is depleting its aquifers, causing groundwater tables to drop nearly 40 feet in the last 20 years.3

Big dams are never the answer, and the Bisalpur Dam is no exception. In 2014, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched an ambitious national program to improve the lives of hundreds of millions of rural Indians by connecting rural households to piped tap water.4 And, while this is theoretically laudable, the truth seems to be more along the lines of a corrupt government working with the big-dam lobby to push a large infrastructure agenda that is stripping local communities of water sovereignty. Circle of Blue reports that local leaders believe household and community rainwater harvesting would offer a more sustainable and resilient solution.5

The local food markets also tell a mixed story. They are bursting with piles of colorful fruits and vegetables and bundles upon bundles of brilliant flower buds used to make garlands and provide offerings. It’s all a visual feast. But, again, there’s an underbelly. The muddy roads are filled with animal waste and growing agrochemical use in the region is killing people and ecosystems6 so the basic building blocks and the traditional foods that should be supporting a healthy population, may or may not be doing so. It’s hard to know.

We happened into the Hindu temple at the City Palace early one day just as the daily morning chanting of the Hare Krishna mantra had begun. We took off our shoes, entered, and walked barefoot to the back of the room where we sat on a couple steps, cross-legged. Just in front of us were a handful of musicians assembled in a semi-circle. We were warmly welcomed into the space—the only white faces in the place—and over time were graciously offered herbs to chew and perfumed cotton to place behind our ears. Our third eyes were dotted with orange bindi—presumably made from turmeric or vermillion powder paste. We watched and listened. As the ceremony progressed, the music and chanting became evermore lively. People continued to stream in. The building energy was palpable, ecstatic even. It felt compelling, even to someone like me—not at all religious and not understanding a word around me. After some time, the ceremony culminated as the stage curtain at the front of the room was raised and a handful of men emerged, doing what I couldn’t see. Soon after and prior to the departure of what now appeared to be thousands of people, we quietly got up from our seats and left the temple. We thanked those around us and were sent off with warm wishes.

For whatever troubles the city might have, this gathering said something about the people and their sense of community, love, music, celebration. It is encounters like this—no matter how brief—that compel me to, in the words of Mae Chevrett, go into the world and to be brave, and to want, to need, to hunger for adventures.

I wish you time to go into the world, in whatever way is most meaningful to you.

xo Wendy

I love hearing what moves people. Leave a comment—I read everything.

Pusalkar, Samidha. (2022). Understanding the Vastu shastra: city planning in walled city of Jaipur. Esempi di Architettura 9. 61-72.

Anand, I., Thampi, A., & Vakulabharanam, V. (2023). Wealth inequality: the Indian case. Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue Canadienne d’études Du Développement, 46(2), 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2023.2212898

Daiman, Amit & Rajpoot, Pushpendra. (2014). Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Ground Water Level Fluctuation in Jaipur Urban Area Rajasthan India. Global Journal of Research and Review 1. 72-78.

Byers, Fraser (July 24, 2024) Skepticism in Rural Northwest India as Modi Government Pushes Big Water Infrastructure Projects Instead of Small-Scale Fixes: Rainwater harvesting, an ancient solution, could counteract fluoride contamination, gender inequality, and a warming climate in the state of Rajasthan. Circle of Blue.

Ibid.

Ajit Singh, SS Jheeba. (2020) Impact of pesticide use on farmer’s health in Sri Ganganagar and Jaipur district of Rajasthan. Journal of Entomology and Zoological Studies 8(5):1494-1498.

It seems almost magical, having just arrived in Kenya, to transport yourself to India. I appreciate the introduction to Jaipur and the calmness of that last encounter.

Going into the world indeed! I loved your account of your jaunt to Jaipur, a city I visited more than 20 years ago. A beautiful, vibrant and complex place, as reflected in your lovely telling, Wendy. Hope you'll be able to visit southern India one day as well.